Baldwin's Rules: A Guide to Ring-Closing Reactions

Struggling with determining the major product of a ring-closing reaction? Wanna know if the cyclization reaction you design for your project is feasible? You may want to learn Baldwin's rules.

In memory of Professor Jack Baldwin (1938-2020)

Introduction: A Puzzling Selectivity

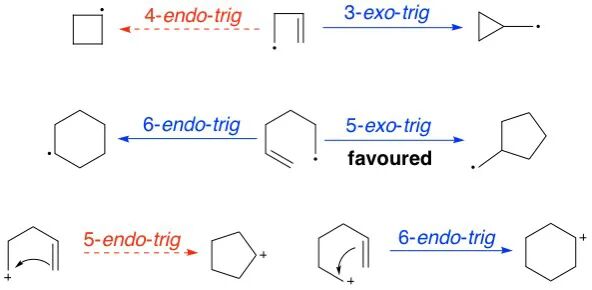

If you’re studying organic chemistry, you’ve probably encountered puzzling questions about cyclization reactions. Consider this: when the same molecule undergoes intramolecular ring closure, and both possible products would form five-membered rings, why does one pathway give 100% yield while the other gives essentially 0% (Scheme 1)?

This selectivity isn’t random—it follows a set of elegant guidelines known as Baldwin’s rules, which help us predict and understand the feasibility of ring-closing reactions.

The Origin of Baldwin’s Rules

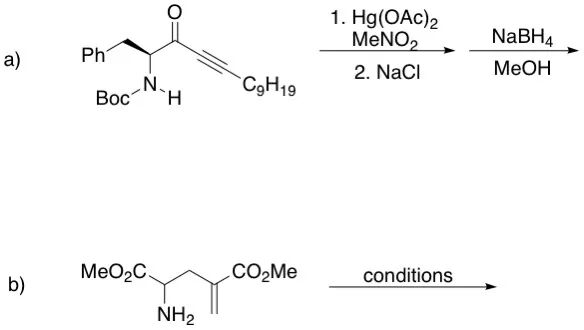

In 1976, British chemist Sir Jack Edward Baldwin systematically analyzed cyclization patterns in acyclic compounds and formulated what we now call Baldwin’s rules. His framework uses three key parameters to describe any ring-closing reaction:

1. Ring Size (n)

A number indicating the size of the ring being formed. For example:

- 5-endo-trig means the reaction is forming a 5-membered ring

- 6-exo-dig means the reaction is forming a 6-membered ring

2. Bond-Breaking Mode

The position of the breaking bond relative to the forming ring:

- exo (exocyclic): The bond being broken lies outside the ring being formed. This ultimately produces a smaller ring.

- endo (endocyclic): The bond being broken lies inside the ring being formed. This ultimately produces a larger ring.

3. Hybridization of the Attacked Atom

- tet: The atom being attacked is sp³ hybridized (tetrahedral)

- trig: The atom being attacked is sp² hybridized (trigonal)

- dig: The atom being attacked is sp hybridized (digonal)

Type of different hybridization of the attacked atom

Type of different hybridization of the attacked atom

The Rules in Detail

Okay, now we know Sir Baldwin described the ring-closing rules by using three key parameters: the ring size (n), the bond-breaking mode (exo and endo), and the hybridization of the attacked atom (tet, trig, and dig). But what exactly are the Baldwin’s rules? How can we use these three parameters to “predict” the major product of a cyclization reaction?

Primarily, Baldwin’s rules can be described as follows:

Rule 1: Tetrahedral (Tet) Systems

For tetrahedral centers, attack from outside the forming ring (exo) is generally favored.

Favorable:

- 3- to 7-membered rings via exo-tet cyclization

Unfavorable:

- 5- to 6-membered rings via endo-tet cyclization

Rule 2: Trigonal (Trig) Systems

For trigonal centers, attack from outside the forming ring (exo) is generally favored, while larger rings (6-7 membered) can accommodate endo-trig closures, but smaller rings cannot.

Favorable:

- 3- to 7-membered rings via exo-trig cyclization

- 6- to 7-membered rings via endo-trig cyclization

Unfavorable:

- 3- to 5-membered rings via endo-trig cyclization

Rule 3: Digonal (Dig) Systems

Digonal systems show different selectivity—endo closures are broadly favorable, while small exo closures are disfavored.

Favorable:

- 5- to 7-membered rings via exo-dig cyclization

- 3- to 7-membered rings via endo-dig cyclization

Unfavorable:

- 3- to 4-membered rings via exo-dig cyclization

The following summary table may give you a more straightforward view:

| Ring Size | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| exo-tet | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| endo-tet | — | — | ✗ | ✗ | — |

| exo-trig | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| endo-trig | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| exo-dig | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| endo-dig | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

(✓ = favored, ✗ = disfavored, — = not commonly observed)

Solving the Opening Puzzle

With the Baldwin’s rules in hand, now we can understand the selectivity shown in the opening example. In the example, the molecule 1-1 can cyclize via two pathways:

- Path A: 5-endo-trig (red-dashed arrow)

- Path B: 5-exo-trig (blue-solid arrow)

According to Baldwin’s rules, 5-endo-trig cyclizations are unfavorable, while 5-exo-trig are favored. This perfectly explains the observed selectivity that 1-2 is the major product in this cyclization (with a yield of 100%).

Extension to Enolate Anions

Baldwin’s rules also apply to cyclizations involving ketone enolate anions, with additional descriptors were added to make the terminology more specific:

- enolendo: The C–C bond of the enolate becomes part of the forming ring

- enolexo: The C–C bond of the enolate lies outside the forming ring

Type of ring-closing type for enolate anions

Type of ring-closing type for enolate anions

The Baldwin’s rules for enolate anions can be described as follows:

- For 6- to 7-membered rings, the enolendo-exo-tet processes are favored.

- For 3- to 5-membered rings, the enolendo-exo-tet processes are disfavored.

- For 3- to 7-membered rings, the enolexo-exo-tet processes are favored.

- For 3- to 7-membered rings, the enolexo-exo-trig processes are favored.

- For 6- to 7-membered rings, the enolendo-exo-trig processes are favored.

- For 3- to 5-membered rings, the enolendo-exo-trig processes are disfavored.

A much more simplified description is:

- For 3- to 5-membered rings, the enolexo processes are favored, while enolendo processes are disfavored.

- For 6- to 7-membered rings, both enolexo and enolendo processes are favored.

This helps explain the following example that why certain ketone cyclizations favor one regioisomer over another based on ring size.

Important Considerations

When applying Baldwin’s rules to the ring closure reaction, one should be aware of the following considerations:

1. “Disfavored” ≠ “Forbidden”

Baldwin’s “disfavored” classification doesn’t mean the reaction is impossible—just that it’s more difficult than the favored cases and may require special conditions or give lower yields. These rules are empirical and have a stereochemical basis. Specifically, the preferred pathways are those where the length and nature of the connecting chain allow the terminal atoms to achieve the appropriate geometries for reaction. In contrast, the unfavorable cases necessitate significant distortion of bond angles and distances.

2. Relative Reactivity Trends for Trig Systems

For Trig systems, sometimes there are more than one favored pathways in the ring closure. In such cases, the general rule will be:

- 5-endo is MUCH MORE FAVORED THAN 4-exo

- 5-exo is more favored than 6-endo

- 6-exo is MUCH MORE FAVORED THAN 7-endo

These trends help predict product distributions when multiple pathways are possible.

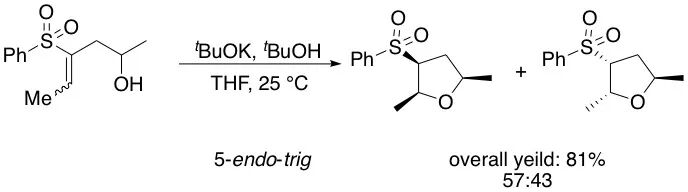

3. Third-Row Elements (S, P, etc.)

When sulfur or other third-row elements participate, sometimes disfavored processes like 5-endo-trig can become feasible. This is attributed to:

Longer C–S bond lengths providing geometric flexibility

Empty 3d orbitals on sulfur that can interact with π bonds

4. Applicability to Cations and Radicals

Baldwin’s rules can also be applied to cationic and radical cyclizations.

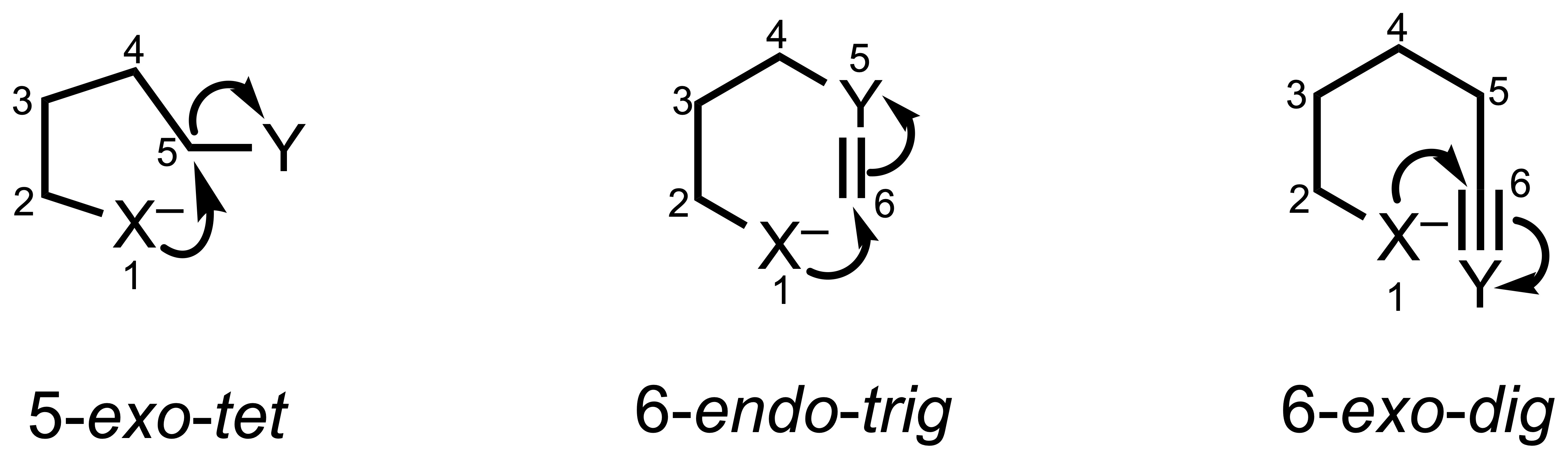

5. Exceptions Exist

Like all empirical rules in chemistry, violations of Baldwin’s rules have been documented. Special structural features, electronic effects, or reaction conditions can override the general trends.

An exception of Baldwin’s rules

An exception of Baldwin’s rules

Practice Time

Well, well, well, as an old saying claims, “practice makes perfect.” Let’s try some practice to see how well you learned from Baldwin’s rules.

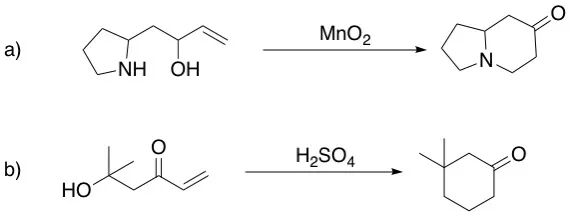

Question 1: Are the following reactions feasible? Why or why not?

a) A 4-exo-trig ring closure reaction b) A 6-endo-dig ring closure reaction

Question 2: Are the following reactions feasible? Why or why not?

Question 3: Finish the following reactions:

(Think through these using the rules above before checking literature or computational predictions!)

A Tribute to Professor Baldwin

Professor Sir Jack Edward Baldwin passed away in January 2020 at the age of 81. His contributions to organic chemistry extended far beyond these rules—he made fundamental discoveries in total synthesis of natural products, mechanisms of reactions, and biomimetic synthesis.

Baldwin’s rules remain one of the most practical and widely used guidelines in synthetic organic chemistry, helping chemists design more efficient syntheses and understand reaction selectivity. His legacy continues to guide researchers in academia and industry worldwide.

Conclusion

Baldwin’s rules provide a powerful framework for understanding and predicting the outcome of ring-closing reactions. By considering three simple parameters—ring size, bond-breaking mode, and hybridization—we can rationalize selectivity that might otherwise seem arbitrary.

Whether you’re planning a total synthesis, analyzing a reaction mechanism, or simply studying for an exam, these rules are an indispensable tool in the organic chemist’s toolkit.

References

- Baldwin, J. E. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun., 734-736 (1976).

- Baldwin, J. E.; Thomas, R. C.; Kruse, L.; Silberman, L. J. Org. Chem., 42, 3846-3852 (1977).

- Johnson, C. D. Acc. Chem. Res., 26, 476-482 (1993).

- Baldwin, J. E.; Kruse, L. I. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun., 233-235 (1977).

- Baldwin, J. E. Tetrahedron 38, 2939-2947 (1982).

- Baldwin, J. E.; Cutting, J.; Dupont, W.; Kruse, L. I.; Silberman, L.; Thomas. R. C. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun., 736-738 (1976).

- Alabugin, I. V.; Gilmore, K. Chem. Commun., 49, 11246-11250 (2013).

- Craig, D.; Ikin, N. J.; Mathews, N.; Smith, A. M. Tetrahedron 5, 13471-13494 (1999).

- Overhand, M.; Hecht, S. M. J. Org. Chem., 59, 4721-4722 (1994).

- Ferry, G. Nature 578, 212 ( 2020).